Oh, the politics of black women’s hair. At the recent Women of the World festival, at London’s Southbank, a session was devoted to debate. And below is an excerpt from an interview in the ‘Telegraph’ with Chimimanda Ngozi Adichie:

Throughout the interview, Adichie has been playing with her hair, which is neatly braided and tucked on top of her head. She’s waiting for me to ask about it. Because hair is everywhere in Americanah. It has taken root as a central theme. Adichie herself is a leading voice in the natural hair movement – which decries the use of relaxers and anything that chemically alters it. And none of her characters escapes having their locks categorised. Indeed, much of the storytelling takes place in an American hair salon, where Ifemelu has gone to have her hair braided.

There are descriptions of cornrows, braids, shiny straight weaves, box braids, comb-overs, natural afros, corkscrews, coils, russet waves and TWAs (Teeny Weeny Afros). And to style them? Pomades, irons, relaxers, oils, butters, moisturisers and creamy conditioners.

So what of her own hair? As a ‘hair fundamentalist’ surely it’s all natural?

Adichie hesitates. “Actually the tips are Afro Kinky extensions, to add volume. Most black women add extensions to their hair. But I argue that they should be like our own hair. We should embrace our natural style.”

Her approach, she admits, leaves her Nigerian friends bemused. She has even been scolded by strangers for not having a straight weave.

“My hairdresser in Lagos says; ‘Why do you want to use this rough hair? Try this one, it’s silky and soft'” says Adichie. “And I say to her; “because it’s like what grows on my head. That’s why”.

When I confess that my poker straight locks often bore me to tears, Adichie sits-up straight.

“You should go public,” she urges. “In Nigeria straight weaves are very desirable and very expensive. I remember once, when I was in a salon in Lagos, a woman came in and paid $800 for a straight weave. And I sat there thinking ‘what? Get the rough hair. It’s about $9!”

I’ve pasted this in full, because sets out the arguments so much better than me. It is a subject especially dear to my heart, especially when there is still that Caribbean divide of ‘good hair’ and ‘bad hair’ – if you’re curly, you better get out that hot comb. In my time, I have had long hair, short hair, straight hair, curly hair, straightened, relaxed and curly-permed hair. I have loxed my hair (twice), plaited it in braids and there are school photos that involve an afro.

So, I am always intrigued by the depictions of ‘black’ hair in children’s books. I want to see women and men that look like my friends and family. But more importantly, I want to children to see themselves and feel proud.

I bought ‘What About Me?’ for my daughter when she was five months old. It was in a bookshop in the Southbank Centre – I saw the cover and grabbed it. (In those days, I used to grab any book that had a brown-skinned child on it, regardless of the quality!) But this story was great – I read it so much I knew it by heart. While I was studying for MA in Sheffield, I used to read it over the phone so her dad could play it on loudspeaker in the car. But… she used to bend over and kiss the little girl’s face. I may be disillusioned, but I’m convinced she used to think it was me.

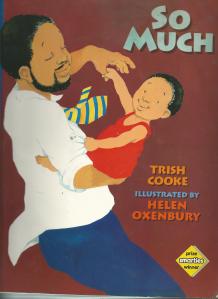

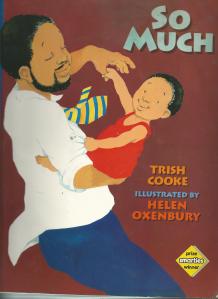

Then there is the wonderful ‘So Much’.  I found this after Googling Helen Oxenbury’s name in the early days of Amazon. (We had a bag full of Helen Oxenbury board books from Booktrust, given to parents when their babies were vaccinated.) In this book, the illustrator does HAIR. Daddy and baby – yup, afro. Mum’s got the braids. Aunty Bibba, hair up, afro-bun. And a headband. (And desert boots!) Uncle Didi? Shaved back and sides, with a flat-top mohican combo. The grannies – handbags and hats.

I found this after Googling Helen Oxenbury’s name in the early days of Amazon. (We had a bag full of Helen Oxenbury board books from Booktrust, given to parents when their babies were vaccinated.) In this book, the illustrator does HAIR. Daddy and baby – yup, afro. Mum’s got the braids. Aunty Bibba, hair up, afro-bun. And a headband. (And desert boots!) Uncle Didi? Shaved back and sides, with a flat-top mohican combo. The grannies – handbags and hats.

At a recent event on equality in publishing, there was a rather tense debate about workforce development. Will a more diverse workforce influence the content of children’s books? Should it? In a global society, should we still be asking that question?

I always used to resent the fact that I had to seek out special ‘black hairdressers’ to get my hair done. In the end, the best hairdresser I ever had was a white guy. The same way, I feel that children’s illustrators regardless of their own ethnic background, should feel able and comfortable to draw our hair and features, sympathetically, stylistically and fit for a baby to kiss.